Facts about the American Bald Eagle

Description

The plumage of an adult bald eagle is evenly dark brown with a white head and tail. The tail is moderately long and slightly wedge-shaped. Males and females are identical in plumage coloration, but sexual dimorphism is evident in the species, in that females are 25% larger than males. The beak, feet and irises are bright yellow. The legs are feather-free, and the toes are short and powerful with large talons. The highly developed talon of the hind toe is used to pierce the vital areas of prey while it is held immobile by the front toes. The beak is large and hooked, with a yellow cere. The adult bald eagle is unmistakable in its native range. The closely related African fish eagle (H. vocifer) (from far outside the bald eagle's range) also has a brown body (albeit of somewhat more rufous hue), white head and tail, but differs from the bald in having a white chest and black tip to the bill.

The plumage of the immature is a dark brown overlaid with messy white streaking until the fifth (rarely fourth, very rarely third) year, when it reaches sexual maturity. Immature bald eagles are distinguishable from the golden eagle (Aquila chrysaetos), the only other very large, non-vulturine raptorial bird in North America, in that the former has a larger, more protruding head with a larger beak, straighter edged wings which are held flat (not slightly raised) and with a stiffer wing beat and feathers which do not completely cover the legs. When seen well, the golden eagle is distinctive in plumage with a more solid warm brown color than an immature bald eagle, with a reddish-golden patch to its nape and (in immature birds) a highly contrasting set of white squares on the wing. Another distinguishing feature of the immature bald eagle over the mature bird is its black, yellow-tipped beak; the mature eagle has a fully yellow beak. The bald eagle has sometimes been considered the largest true raptor (accipitrid) in North America. The only larger species of raptor-like bird is the California condor (Gymnogyps californianus), a New World vulture which today is not generally considered a taxonomic ally of true accipitrids. However, the golden eagle, averaging 4.18 kg (9.2 lb) and 63 cm (25 in) in wing chord length in its American race (A. c. canadensis), is merely 455 g (1.003 lb) lighter in mean body mass and exceeds the bald eagle in mean wing chord length by around 3 cm (1.2 in). Additionally, the bald eagle's close cousins, the relatively longer-winged but shorter-tailed white-tailed eagle and the overall larger Steller's sea eagle (H. pelagicus), may, rarely, wander to coastal Alaska from Asia.

Range

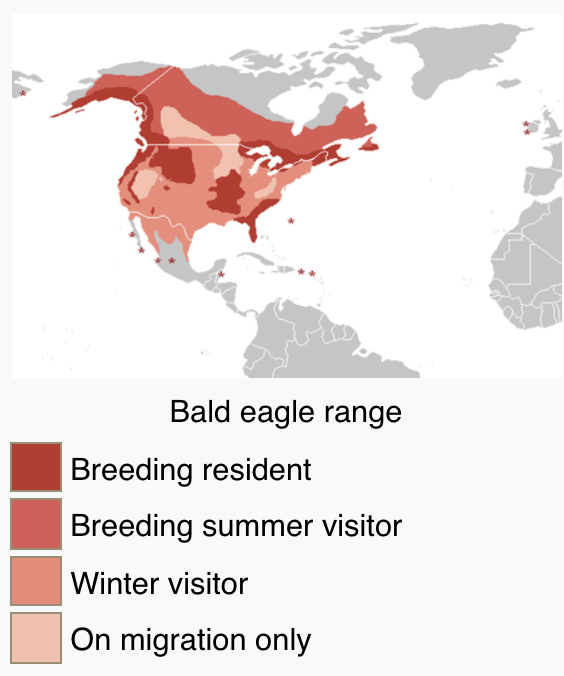

The bald eagle's natural range covers most of North America, including most of Canada, all of the continental United States, and northern Mexico. It is the only sea eagle endemic to North America. Occupying varied habitats from the bayous of Louisiana to the Sonoran Desert and the eastern deciduous forests of Quebec and New England, northern birds are migratory, while southern birds are resident, remaining on their breeding territory all year. At minimum population, in the 1950s, it was largely restricted to Alaska, the Aleutian Islands, northern and eastern Canada, and Florida. During the interval 1966-2015 bald eagle numbers increased substantially throughout its winter and breeding ranges, and as of 2018 the species nests in every continental state and province in the United States and Canada.

The majority of bald eagles in Canada are found along the British Columbia coast while large populations are found in the forests of Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba and Ontario. Bald eagles also congregate in certain locations in winter. From November until February, one to two thousand birds winter in Squamish, British Columbia, about halfway between Vancouver and Whistler. The birds primarily gather along the Squamish and Cheakamus Rivers, attracted by the salmon spawning in the area. Similar congregations of wintering bald eagles at open lakes and rivers, wherein fish are readily available for hunting or scavenging, are observed in the northern United States. It has occurred as a vagrant twice in Ireland; a juvenile was shot illegally in Fermanagh on January 11, 1973 (misidentified at first as a white-tailed eagle), and an exhausted juvenile was captured in Kerry on November 15, 1987.

Habitat

The bald eagle occurs during its breeding season in virtually any kind of American wetland habitat such as seacoasts, rivers, large lakes or marshes or other large bodies of open water with an abundance of fish. Studies have shown a preference for bodies of water with a circumference greater than 11 km (7 mi), and lakes with an area greater than 10 km2 (4 sq mi) are optimal for breeding bald eagles.

The bald eagle typically requires old-growth and mature stands of coniferous or hardwood trees for perching, roosting, and nesting. Tree species reportedly is less important to the eagle pair than the tree's height, composition and location. Perhaps of paramount importance for this species is an abundance of comparatively large trees surrounding the body of water. Selected trees must have good visibility, be over 20 m (66 ft) tall, an open structure, and proximity to prey. In a more typical tree standing on dry ground, nests may be located from 16 to 38 m (52 to 125 ft) in height. In Chesapeake Bay, nesting trees averaged 82 cm (32 in) in diameter and 28 m (92 ft) in total height, while in Florida, the average nesting tree stands 23 m (75 ft) high and is 23 cm (9.1 in) in diameter. Trees used for nesting in the Greater Yellowstone area average 27 m (89 ft) high. Trees or forest used for nesting should have a canopy cover of no more than 60%, and no less than 20%, and be in close proximity to water. Most nests have been found within 200 m (660 ft) of open water. The greatest distance from open water recorded for a bald eagle nest was over 3 km (1.9 mi), in Florida. Bald eagle nests are often very large in order to compensate for size of the birds. The largest recorded nest was found in Florida in 1963, and was measured at nearly 10 feet wide and 20 feet deep.

The bald eagle is usually quite sensitive to human activity while nesting, and is found most commonly in areas with minimal human disturbance. It chooses sites more than 1.2 km (0.75 mi) from low-density human disturbance and more than 1.8 km (1.1 mi) from medium- to high-density human disturbance.[40] However, bald eagles will occasionally nest in large estuaries or secluded groves within major cities, such as Hardtack Island on the Willamette River in Portland, Oregon or John Heinz National Wildlife Refuge at Tinicum in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, which are surrounded by a great quantity of human activity. Even more contrary to the usual sensitivity to disturbance, a family of bald eagles moved to the Harlem neighborhood in New York City in 2010.

Facts

Diet and Feeding

- The bald eagle is an opportunistic carnivore with the capacity to consume a great variety of prey. Throughout their range, fish often comprise the majority of the eagle's diet.

- In 20 food habit studies across the species' range, fish comprised 56% of the diet of nesting eagles, birds 28%, mammals 14% and other prey 2%

- Southeast Alaskan eagles largely prey on pink salmon (Oncorhynchus gorbuscha), coho salmon (O. kisutch) and, more locally, sockeye salmon (O. nerka), with chinook salmon (O. tshawytscha)

- In Oregon's Columbia River Estuary, the most significant prey species were largescale suckers (Catostomus macrocheilus) (17.3% of the prey selected there), American shad (Alosa sapidissima; 13%) and common carp (Cyprinus carpio; 10.8%).

Longevity and mortality

- The average lifespan of bald eagles in the wild is around 20 years, with the oldest confirmed one having been 38 years of age.

- In captivity, they often live somewhat longer; a captive individual in New York lived for nearly 50 years.

- The average lifespan of an eagle population appears to be influenced by its location and access to prey

- Most non-human-related mortality involves nestlings or eggs. Around 50% of eagles survive their first year.

- The bald eagle will defend its nest fiercely from all comers and has even repelled attacks from bears, having been recorded knocking a black bear out of a tree when the latter tried to climb a tree holding nestlings.

Reproduction

- Bald eagles are sexually mature at four or five years of age. When they are old enough to breed, they often return to the area where they were born.

- It is thought that bald eagles mate for life. However, if one member of a pair dies or disappears, the survivor will choose a new mate.

- A pair which has repeatedly failed in breeding attempts may split and look for new mates.

- Bald eagle courtship involves elaborate, spectacular calls and flight displays. The flight includes swoops, chases, and cartwheels, in which they fly high, lock talons, and free fall, separating just before hitting the ground.

- Usually, a territory defended by a mature pair will be 1 to 2 km (0.62 to 1.24 mi) of waterside habitat.

Population decline and recovery

- Once a common sight in much of the continent, the bald eagle was severely affected in the mid-20th century by a variety of factors, among them the thinning of egg shells attributed to use of the pesticide DDT.

- Female eagles laid eggs that were too brittle to withstand the weight of a brooding adult, making it nearly impossible for the eggs to hatch.

- It is estimated that in the early 18th century, the bald eagle population was 300,000–500,000, but by the 1950s there were only 412 nesting pairs in the 48 contiguous states of the US.

- The species was first protected in the U.S. and Canada by the 1918 Migratory Bird Treaty, later extended to all of North America.

- The Bald and Golden Eagle Protection Act, approved by the U.S. Congress in 1940, protected the bald eagle.